Why this course | About the course | Course process | The value of communication | iCARE-Haaland model resources

Communicating with awareness and emotional competence:

Strengthening skills to interact respectfully, for health professionals across cultures.

(iCARE-Haaland model)

|

Click here to view this video in full screen. |

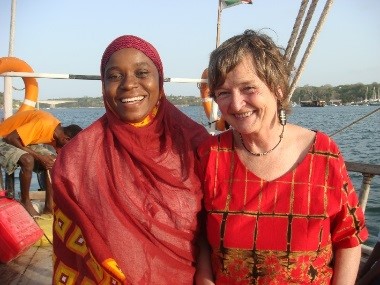

Ane Haaland (University of Oslo, Norway) with Mwanamvua Boga (KEMRI -Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kenya).

Process training developed and implemented in collaboration with physicians and nurses in Lithuania, Latvia, Russia, UK/Wales, Kenya, Zambia, Namibia, Gambia and Tanzania Communication skills training iCARE overview (pdf) |

Why this course

Being a healthcare professional is a privilege and often very rewarding, but it can also be challenging and tough for the individuals providing the care.

Most patients when they are ill and vulnerable want to feel cared for and safe, to be treated as a person and met with empathy, compassion and competence. Healthcare professionals want to offer this kind of care as they are motivated by an underlying desire to help, an attitude of respect, and the intention of having a high-quality impact.

Yet, research and experience from around the world report widespread incidences of disrespectful care and abuse of patients and bullying among colleagues. The underlying reasons are many.

While meeting the emotional challenges involved in caring for others is an implicit part of the relationship between a healthcare professional and a patient, the skills to manage them are rarely taught. It is no wonder that so many healthcare professionals find themselves unable to cope, and many decide to leave the profession. They experience constant stress leading to burnout, bullying and conflicts, and many develop emotional difficulties or mental illness which are often taboo to even acknowledge, much less treat.

Pressures on healthcare professionals are many, and increasing: They are expected to deliver ever more and better care, more obligatory documentation, at a lower cost and within an aging infrastructure.

In the midst of all this stress and emotional challenge, the unspoken presumption is that they will take care of their own emotional needs while continuing to communicate with awareness and respect for patients and colleagues. This presumes they have the skills and knowledge to do so, that they have the time to do this, and that they will be supported by the system as they do so. Each of these three pieces is essential to success.

Helping healthcare professionals develop this essential skill set is what the iCARE-Haaland model is designed to do. This training has been proven to help healthcare professionals to develop emotional competence and to communicate with awareness and respect, improving their own well-being and job satisfaction, and caring better for patients. It does not solve all the problems in the health systems, but it does help professionals function better in the system within which they are to provide care. Over time, those changes may enter the system as a whole so that humanistic care serves as its foundation.

About the course

Siauliai, Lithuania 2006: Virgaine Bielskiene, Siauliai, Lithuania 2006: Virgaine Bielskiene, Jurate Kaupiene and Andzelina Skerbiene Photo: Ane Haaland |

Kenya 2016:Mwanamvua Boga and Ane Haaland Kenya 2016:Mwanamvua Boga and Ane HaalandCredit: Ayub Mpoya |

Developing the model: iCARE refers to its main components: intelligent Communication, Awareness and Action, Reflection, Emotions. Within Reflection is included Observation – In Action, and On Action. The model has been developed and implemented over a period of 14 years, starting in Lithuania in 2006. Since 2009, the focus for further development has been with medical staff mainly in Kilifi, Kenya and with trainee medical doctors in Wales, UK in 2016-17. A deep respect for the work and personal challenges of these professionals is a basis for contents and methods.

There are vast differences in local cultures and traditions between e.g Lithuania, Kenya, UK and Namibia. Despite this, and despite differences in access to personnel and resources, the concerns and needs of the 350 participating health professionals over these years have proved to be surprisingly similar: managing emotions was seen as the most important learning. To address their needs, training aims are designed to improve participants’ capacity to:

- Build safe and trusting relationships;

- Provide patient-centred care (PCC);

- Communicate and relate well with colleagues;

- Build emotional competence, and

- Take better care of their own health and wellbeing.

Within the context of the participants’ workplace and relationships, communication is taught as a set of interweaving and interdependent skills and attitudes, with emotions serving as a natural resource. Cultural norms are challenged with respect and in collaboration with the participants. Strengthening self-awareness is key in all that is taught.

NOTE: The use of content from this manual for all non-commercial education, training and information purposes is encouraged but there should be full acknowledgement of the source as follows, and where material is adapted, this should be clearly stated:

Haaland A, with Boga M, 2020. Communicating with awareness and emotional competence: introducing the iCARE-Haaland model for health professionals across cultures. With contributions from training teams, Vicki Marsh and Sassy Molyneux.

Available at: https://connect.tghn.org/training/

Contacts: ane.haaland@gmail.com

The History of the model and how it was developed – a personal story [PDF, 4.4mb].

Course Process

Consisting of a four-phase program, participants volunteer for the 9-month course:

|

Phases |

Activity |

Duration |

Aim |

Materials included |

|

1 |

Self-observation “in action” and reflection to discover, using guided weekly tasks, on a set of specific aspects of communication and emotions. Monthly meetings to discuss learning; distribute new tasks |

1–4 months

On the job/ during regular work hours |

Strengthen participants’ self- awareness about their own communication behaviors and the effects when dealing with patients and colleagues, and start a change process. |

Baseline questionnaire Guides for analyzing O&R tasks and prepare for training |

|

2 |

Basic Workshop: Interactive reflection – Experience based learning methods, including results from observation and reflection |

½–5 days * Central place/ full time |

Skills training, with feedback. Linking participants’ own observations to a number of theories. |

TOT notes |

|

3 |

Skills into practice: Informed reflection in and on action. Continue self-observation + reflection during daily routine work, using specific tasks to deepen + confirm learning |

3–4 months On the job/ during regular work hours |

Practice new skills in their own working environment; discuss with colleagues; become a role model. Strengthen confidence to practice new skills. |

Observation and reflection tasks |

|

4 |

Follow-up workshop: Interactive and informed reflection. Further training based on results from observations, to summarize and anchor learning to daily challenges faced by participants |

½–4 Days* Central place/ full time |

Deepen understanding of issues, especially on handling “difficult” emotions. Confirm and appreciate learning; strengthen confidence; empowerment. |

TOT notes |

*Nb. This is the recommended period for the workshops but in some contexts, this may need to be adjusted to accommodate the availability of participants, and in such instances, it may require the workshops to occur over a longer timeframe.

Why are the tasks essential to the training? The innovative ways of using self-observation and reflection-in-action enables insights that stir an inner motivation to change how participants communicate and relate emotionally with patients and colleagues. Nobody tells them what to do. They discover it – and because they want to give the best care, they change, when they have a good reason to do so. When they see the new methods working better, they adopt them, and hardly look back. They are empowered to learn, in their own way.

The workshops: Participants’ discoveries and insights from the observation tasks are included in workshop modules, thus validating their independent work and linking the learning firmly to their workplace reality. Using interactive reflections, the workshop process also helps link practical insights to relevant theories from several fields. The group work helps participants realize that they are not alone in the challenges and shortcomings they face, which again strengthens motivation to learn.

Success depends on good trainers: Trainers must be skilled in facilitating learning, using experiential methods and establishing a safe learning environment where mutual respect is the ground rule. They must lead supportive group practices where interactive reflection, critical thinking and expressing appreciation are key. Trainers must guide, explore and inspire participants’ curiosity to find reasons behind their own and others’ actions, behaviours and problems – rather than judge them for what they do, and don’t manage to do. Emphatic understanding and appreciation are important skills they use, and teach.

Results: Often, participants ask, “Why didn’t anyone teach us these skills before?” The majority of the course participants said emotional management was their most important learning – and that they did not know they needed these skills. They learnt to recognise their emotions, step back from automatic reactions and take responsibility for communicating with awareness and respect.

The majority report that they have largely met their aims through the learning process. They now have tools to understand themselves, their colleagues and their patients better: They see that improvement is possible, and – it is their own. An independent research evaluation in Kenya confirmed the self-reported changes participants describe: They have better relationships with patients and colleagues, and they take responsibility for communication rather than blaming others. They experience fewer conflicts, less burnout, and they enjoy their work more.

What value do communication skills bring to my work as health worker?

- Reflections of participants [PDF, 668kb]

- Using skills with patients gives you energy – Dr Kairuni Doto ( Medical Officer), Christine Ososi ( Occupational therapist), and Mwanamvua Boga. Watch the video here.

- Three health care providers reflect on usefulness of skills within their work context – Christine Ososi (Occupational therapist), Priscilla Ndhuli ( Nurse), Dr Kairuni Doto ( Medical Officer), Mwanamvua Boga (Nurse and educator). Watch the video here.

- Caro on the impact of training 9 years on – interview with Caroline Mulunda (Clinical officer in Kilifi, Kenya)

Caroline Mulunda says communication is quite easy – when you respect your patients and really decide to listen to what their needs are. “Whatever reaction a patient has – it comes from their needs. We should not be harsh and judge automatically what they do or say, but find out what is behind their reaction. Patients are very willing to talk, when they sense that you are there for them”, she says with a gentle smile.

Caro is a Clinical Officer at Kilifi District Hospital and was very pregnant when participating in the first communication skills workshop in 2010, which lasts for five days. In the late afternoon on day 4 of the workshop, Caro said quietly that she might not join us the last day, and was sorry to miss it. At 9pm, she delivered her baby, known by all as “The Communication Boy”.

“Active listening, with understanding and empathy, is the most important skill”, says Caro, and adds that when you are aware and control your reactions, you get a positive outcome at the end of the day.

“All health providers should learn these communication skills in their basic training”, says Caro, and adds that her skills to communicate with awareness and emotional competence are now an integrated and important part of her practice. Watch the video here.

- Using Communication and Emotional Competance skills – interview with Zubeda Amazeje (Nurse)

“When you understand how to talk to clients nicely, you are satisfied at the end of the day”, says Zubeda Amazeje, a nurse manager in Kilifi district hospital. “Many staff are rude, and I used to be rude to patients myself. Now, if I see they are rude, I go and apologize to the patient, and then talk with the staff member, privately”, she says, and adds that her team is now the best in the hospital. Zubeda acts fast when she discovers a problem: She finds out what is the reason behind the problem, and she solves it.

Zubeda is well known in the hospital for taking on staff who others found difficult to work with. She takes them on, listens to them, finds the reasons for their problems, empathizes, and gives them a chance. “These staff have families who are dependent on them, and they deserve a chance”, says Zubeda, and adds that she makes it clear that they have to take responsibility for what they do.

“Community members do not understand us, and we do not understand them. They have a lot of fear, and when we use our communication skills to welcome them and remove the fear, they will open up and cooperate with us. We have to take the responsibility to handle the situation well”, says Zubeda, and adds that the skills to communicate and manage emotions should be taught everywhere – not just to health workers. Watch the video here.